Going Forth

Going Forth is a handmade artist’s book created between 2021-2022 as a way to process concepts of aging, life, death and self-improvement during a pandemic. The book utilizes themes, materials and concepts related to the Egyptian Book of the Dead (The Book of Going Forth by Day), drawing connections to both personal growth and the history of photography.

Central to Going Forth is a rumination on the concept of MUMIA – a concept with multiple related and yet vastly different meanings.

The initial meaning of mumia was Bitumen of Judea (also known as asphaltum), a material used as a binding agent in the wrapping of Egyptian mummies. This was the root of the English word “mummy.”

In Medieval Europe, mumia came to mean actual ground up mummies – the powder being marketed medicinally, customers ingesting the mumia orally.

Both types of mumia were tested as paint pigments. Bitumen was found to lack archival stability, but the powdered remains of mummified humans was used as pigment, creating “Mummy Brown” oil paint.

Paracelsus wrote at length regarding his personal definition of Mumia.

“The Mumia, or vehicle of life, is invisible, and no one sees it depart; but nevertheless it is a spiritual substance containing the essence of life, and it can be brought again by art into contact with dying forms, and revive them, if the vital organs of the body are not destroyed. That which constitutes life is contained in the Mumia, and by imparting the Mumia we impart life.”

Of particular interest during the creating of GOING FORTH was Paracelsus’s discussion of Mumia in relation to vaccines:

“MUMIA.—The essence of life contained in some vehicle. (Prana, Vitality; clinging to some material substance.) Parts of the human, animal, or vegetable bodies, if separated from the organism, retain their vital power and their specific action for a while, as is proved by the transplantation of akin, by vaccination, poisoning by infection from corpses, dissection wounds, infection from ulcers, etc. (Bacteria are such vehicles of life.) Blood, excrements, etc., may contain vitality for a while after having been removed from the organism, and there may still exist some sympathy between such substances and the vitality of the organism; and by acting upon the former, the latter may be affected.”

The earliest known saved photographic image – 1827 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce

Bitumen of Judea is important in the history of photography as it was a key component of the emulsion utilized by 1827 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in the first viable photographic process. Niépce would call the resulting image a Heliograph – “sun drawing.”

Bitumen of Judea is itself formed of the remains of long-dead organisms, thus adding another layer to the meditation on mortality. The pungent material also has a tangential contemporary occult connection, being the key ingredient that allowed occultist and rocket scientist Jack Parsons to formulate a solid fuel capable of propelling rockets further and longer than before. Some accounts state that Parsons was in part inspired by the ancient use of asphaltum in manufacture of the incendiary weapon known as “Greek Fire.” Thus, a material containing elements of life and of death, of the terrestrial and the cosmic.

The book pages are made of photographic prints – self-portraits which have been modified with an intentional misuse of Niépce‘s Heliograph process. Where Niépce applied the asphaltum emulsion to metal plates, I subverted photography’s general focus on archival preservation by considering mumia’s failed history as a paint pigment, applying the emulsion to the surface of pre-existing photographs. Negatives of found images – including pages from the Book of the Dead & Paracelsus’s notes on Mumia – were laid on top of the coated prints and left in the sun to expose. This provided an extra layer, both visually and conceptually, to each page.

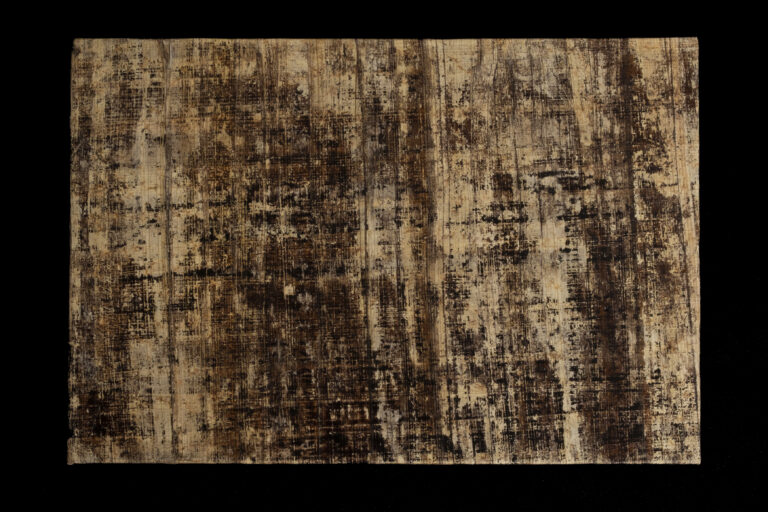

The book cover was created in a similar fashion, though the base layer was Egyptian papyrus rather than a photographic print.

The pages of the book when unfolded are the same length as I am tall – a reference to ancient Egypt’s units of measurement being based on human body parts (ex. the width of a finger, hand, etc.).

The accordion format was inspired by various ancient spellbooks, including this example as found in the British Museum.

The Books of the Dead were originally custom made for an individual, a scribe commissioned to include the selected spells of the modular book that would best assist in aiding one in the afterlife.